Background

The Communist Manifesto was first published in London in 1848.

It’s interesting to note both the time and the place that the manifesto was published. 1848 was the heart of the Industrial Revolution and London was the capital city of England, where the Industrial Revolution first started.

The manifesto was a direct response to the Industrial Revolution and the fear that it would create a permanent underclass (the proletariat or the oppressed) while a select few reaped all the gains (the bourgeoisie or the oppressors).

Its authors — Frederick Engels and Karl Max — are often considered the fathers of modern communism and if you have read my posts before, you know I am a staunch supporter of capitalism.

So you might justifiably be asking: why did you read The Communist Manifesto?

Well I can’t help but notice similarities between the Industrial Revolution and what is happening today with Artificial Intelligence.

I wanted to go back and read what people were saying at the time to see if there is anything we can learn for the 21st century.

With that in mind, we will cover the good, the bad and the ugly of The Communist Manifesto.

The Good

Marx and Engels argued that there has always been a class war.

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.

However, these class struggles were always limited by the available technology. Medieval kings gained power through the serfs and guildsmen they protected. Those serfs farmed the land with horses and rudimentary plows. The guildsmen produced clothes, swords, and other goods by hand.

For a king to become more powerful, he needed to have more people and more land under his control. It was the only way to scale.

This was true for medieval kings, Roman emperors, and Egyptian pharaohs.

While certain tools were created — the domestication of horses, ironworks, guns — that gave the oppressors more power, none of these tools compared to the Industrial Revolution.

The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground – what earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labour?

All of these technologies were a part of the Industrial Revolution which — for the first time — created real leverage to human capital:

The Roberts Loom allowed weavers to product 10-15x as much cloth as before

The McCormick Reaper allowed farmers to harvest 10-24x as many acres as before

This leverage terrified Marx and Engels.

Note: If you were wondering about communists’ obsession with “the means of production” it’s because machines and capital were replacing human labor’s role in producing goods.

While there was always a power imbalance between the oppressors and the oppressed, the oppressors needed the oppressed. They relied on the oppressed because the oppressed manual labor was key to their power.

With the Industrial Revolution, would the oppressors need the oppressed?

With 10x improvements in making clothes and harvesting food, would 90% of weavers and farmers be out of their job?

With previously skilled jobs turning into unskilled, replaceable roles, would wages plummet for the few people who were still employed?

And what would the oppressors do with their new power? Would they build new machines that would give them even more money? Which would put even more of the oppressed out of work?

This cycle might continue until the oppressors established a permanent advantage over the oppressed.

Or at least that’s what Marx and Engels argued.

The Bad

Well it turns out that almost everything Marx and Engels predicted was wrong.

If we just look at England (who was the most industrialized at the time):

Average real wages of workers doubled between 1819 and 1851

Roughly two-thirds of the population lived in poverty in 1800 compared to less than a third in 1900

Average life expectancy went from 39 years in 1800 to 47 years in 1900

Seems pretty good! But one could argue that maybe all of the gains from the Industrial Revolution were going to England and the rest of the world was suffering.

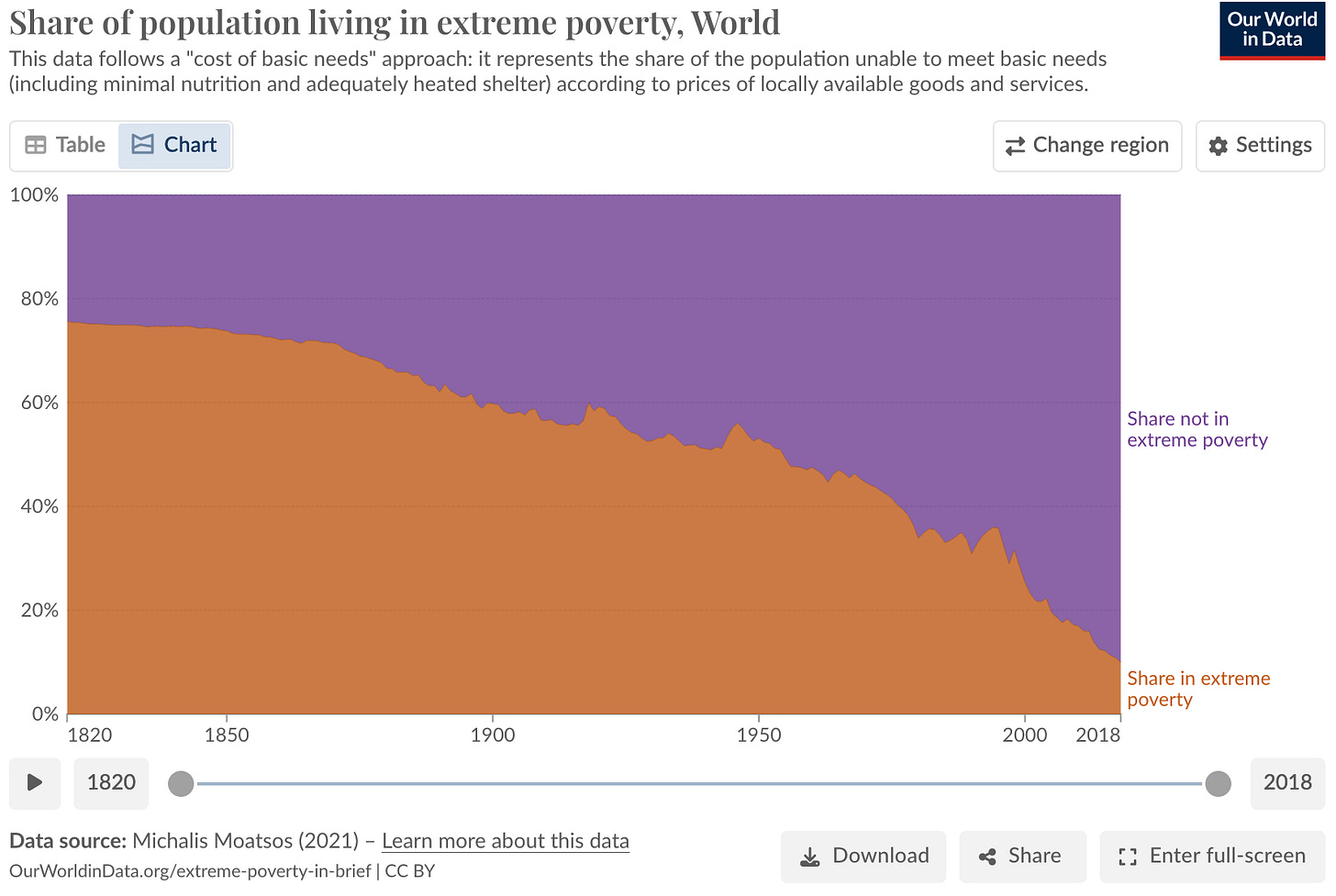

I couldn’t find data from prior to 1820 but you can see that extreme poverty levels went from over 75% in 1820 to below 60% in 1900. And today it sits below 20%.

Pretty good indeed! The question then becomes why were Marx and Engels so wrong?

The pie grows

Marx and Engels (and many people today) have a view that the size of the pie is fixed. If one person decides to take more pie, it is coming at the direct expense of someone else.

Instead, the Industrial Revolution created more pies.

In our example above, Marx and Engels were worried about 90% of weavers losing their jobs because innovations in technology allowed people to produce 10-15x as much cloth as before.

What happened instead, is that factory owners decided to produce more cloth. And often, they didn’t produce 10-15x as much cloth, they decided to produce 100x more cloth, which actually led to increased employment.

They were able to do this because the innovation in weaving technology allowed them to drop the price of cloth, which enabled more people to purchase it.

If you read stories about people living in the 1700s, they typically owned one or two outfits that they sowed and mended themselves.

Once clothes became cheaper, people started buying additional outfits and now you have the fast fashion of the 21st century where people switch out their closets each season.

This story was true across almost every industry.

Innovation in production reduced prices

Reduced prices increased demand

Increased demand increased supply (and often increased employment)

New institutions are born

The Industrial Revolution also led to a massive increase in unions. The huge swaths of unskilled workers banded together to increase their negotiating power.

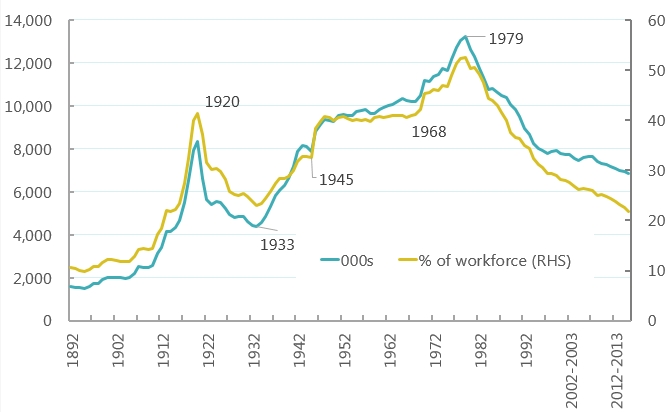

To give Marx and Engels credit, it did take time for these unions to gain power. Unions membership didn’t peak until 1979, 131 years AFTER their manifesto was published. But union membership peaked at an astounding 50% of the working population in the UK.

And unions are not the only way to cure the imbalance.

Countries across the world created regulations to protect workers. For example, here is a timeline of regulations in the US:

Sherman Antitrust Act (1890): Prohibit monopolies and unfair business practices that restricted competition.

Clayton Antitrust Act (1914): Strengthened the Sherman Antitrust Act by specifically prohibiting certain anti-competitive practices.

Norris-LaGuardia Act (1932): Limited courts’ ability to issue injunctions against non-violent labor disputes.

National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) (1935): Guaranteed workers the right to form unions and engage in collective bargaining.

Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) (1938): Established minimum wage, overtime pay, and restrictions on child labor.

Again, to give Marx and Engels credit, these laws took time to be created. But my point is that even if technologies were to create power imbalances, institutions will pop up (namely, unions and legislation) to help cure them.

These institutions will always be lagging but I think the massive improvement to living standards we have seen make the trade off worth it.

Innovations lead to more innovations

Marx and Engels believed that the Industrial Revolution was going to be a one-time event that would create a permanent upper class.

To switch from the UK to the US, this would mean that the great Robber Barons of the late 1800s (Rockefeller with Standard Oil, Carnegie with U.S. Steel, Vanderbilt with his shipping and railroad empires, the Morgan Family, etc.) would all still be the richest, most powerful people in the country.

Well…. let’s take a look at the richest people in the world at the beginning of 2024.

Every single one of these people created their own company and three of the top four created their wealth in the last 30 years.

The first “old money” person on the Forbes list is Francoise Bettencourt Meyers, the granddaughter of the founder of L’Oreal. She is 15th in the world and I’d like to note that L’Oreal is French, hardly the bastion of free market capitalism.

What Marx and Engels didn’t understand is that the Industrial Revolution would then be supplanted by the Computer Revolution which would then be supplanted by the Internet Revolution which might currently be being supplanted by the AI Revolution.

If anything, the Industrial Revolution allowed for MORE shifting of power because new technologies could always beat older, existing companies. This is very different from the pseudo-permanent aristocracy of 18th century Europe.

The ugly

I try not to judge writers from a different time but I was definitely surprised by a few passages.

Here is Marx and Engels effectively saying that the new class of workers were worse off than slaves?

The slave is sold once and for all; the proletarian must sell himself daily and hourly. The individual slave, property of one master, is assured an existence, however miserable it may be, because of the master’s interest. The individual proletarian, property as it were of the entire bourgeois class which buys his labour only when someone has need of it, has no secure existence. This existence is assured only to the class as a whole. The slave is outside competition; the proletarian is in it and experiences all its vagaries. The slave counts as a thing, not as a member of society. Thus, the slave can have a better existence than the proletarian, while the proletarian belongs to a higher stage of social development and, himself, stands on a higher social level than the slave.

And another passage arguing that the fact that the Industrial Revolution provided more opportunities for women was a bad thing?

The less the skill and exertion of strength implied in manual labour, in other words, the more modern industry becomes developed, the more is the labour of men superseded by that of women. Differences of age and sex have no longer any distinctive social validity for the working class. All are instruments of labour, more or less expensive to use, according to their age and sex.

Anyway, the book itself was a short read and a fascinating glimpse into the 19th century but 10/10 would NOT recommend listening to Marx and Engels.

TL;DR

The Industrial Revolution upended everything. From social orders to economic systems to how countries interacted with each other.

This chaos caused a lot of fear. What would the new system look like? Would people be protected? Would too much power be in too few hands?

This fear led to sympathies for communism, which promised to protect people against the newly powerful industrialists. (the “oppressors”)

While Marx and Engels may have been well intentioned — they wanted to help people! — all of their fears turned out to be unfounded and society massively benefited from the Industrial Revolution. And even worse, every country that tried to implement communism — the USSR and China most famously — ended with mass starvation, Gulags, authoritarian leaders, etc.

This exact story could be said about the current AI Revolution. White collar workers will be put out of work en masse, inequality will increase, the power will be concentrated in too few hands. Instead of the hammer and sickle, it will be the desk chair and computer.

To me, we should default to this revolution being GOOD and the burden of proof falls on the fear mongers to prove otherwise.